To say that astrophotography in Cumbria is “hit and miss” would be an understatement. It is mostly miss. Cumbria, home to The English Lake District, is probably the wettest county in the UK. When we are not catching the wet weather fronts coming in every few days from the Atlantic, the terrain tends to generate its own weather system, which is likewise cloudy and wet. This forecast is not untypical:

Against this backdrop, my astrophotography is based on a simple (EQ3-2) equatorial mount, an RA motor with rechargeable batteries, and my trusty Nikon D90 with a small collection of reasonably good lenses. My favourite piece of kit at the moment is the WiFi SD card, which means I can review shots immediately on the iPad rather than on the back screen of the camera. The temptation of further investment in hi-tech astrophotography kit is a constant companion, but yielding would only serve to heighten the frustration (by increasing the sunk cost) of all those cloudy nights.

I guess it follows that every outing is tempered with fairly low expectations, as conditions can appear good, then change at a moment’s notice. On this particular night, my expectations were on the low side – the forecast of “clear intervals” and humidity around 90%, were not very encouraging for a target low on the horizon. However, my good friend Stuart Atkinson from the Eddington Astronomical Society had texted the previous evening and persuaded me to set my alarm for 3.30am, so I set about planning for our excursion.

My plan for all sessions follows the same rules: (i) examine the star chart to plan the frame and check the timetable, (ii) go to the chosen location and set up whatever the prospects, (iii) don’t be disappointed if the forecast is wrong.

Get the idea? How I envy those with reliable clear skies!

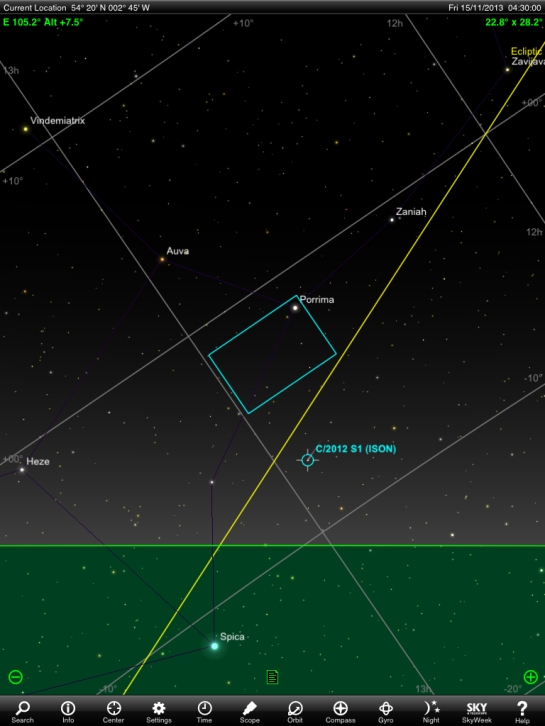

Rule number one, check the star chart. On the morning of 15 November, ISON would rise at 04:05 and astronomical twilight would begin at 05:34. That meant a window of 89 minutes, but for the first 40 of those ISON would be below 5 degrees. Okay, set up and be ready by half past four, leaving an hour for capture.

At 03:30 the alarm goes off and a quick glance through the curtains suggests a “reasonable” sky. Load the car, drive past Stuart’s to collect him, then off we go to the east of town where there is a good view to the eastern horizon across open countryside. There is a small hill which, viewed from my observing spot, is perfectly shaped and positioned so that the ecliptic glides up above the left-hand slope. I have used this location several times over the last month or so.

When we arrive and take a look, I realise to my embarrassment that the ecliptic has moved south since my last excursion, and is now behind the hill. Oops! Stuart politely mutters something about “a mistake anyone could make” as we jump back in the car and head for the next best situation, a small car park about a mile further north. Unfortunately this car park is on the western side of the main road, so by looking east we will have to put up with the headlights from any pre-dawn traffic.

There is a bank of cloud on the eastern horizon, but it looks to be quite mobile. Rule number two kicks in – always set up the mount and point the camera in the right direction. If conditions improve, there might not be time to set up later. My routine is sufficiently well practised that I can unload the mount from the back of the car and be polar aligned well enough for five-minute exposures at 300mm focal length in just a few minutes. As always, I use the tripod unextended for stability, which means kneeling down to squint up through the polarscope while holding a small red torch to illuminate the reticle. In a couple of minutes, Polaris is sitting nicely in the hole and I can clamp the camera to the mount.

So where’s ISON then? I have memorised this grab from the star chart:

That’s my camera frame on Porrima, in the constellation of Virgo, set at 4.5 x 3.0 degrees for the 300mm lens. If I place Porrima in the top right corner of the frame, then slide exactly one frame down the declination axis, ISON will be in the bottom left corner. So where’s Porrima? Here’s the first test shot:

Porrima top right, then slide one frame down and…

Cloud. My eye is drawn to the smudge dead centre. I now know this to be elliptical galaxy NGC 4697, but in my mind ISON will look like a smudge, and there’s a smudge dead centre. I start to doubt my calculation and my preparation to such an extent that I miss the comet lurking behind the cloud at bottom left – exactly where it should be.

Back to Porrima, slide down the Dec axis again, that didn’t feel right, do it again, nudge it a little bit further (why did I do that?), wait a moment for the clouds to move, and grab another test shot. All this while chatting with Stuart about clouds, traffic, whether our luck will change, whether it was worth it anyway, and suddenly…

What on Earth is THAT??? I stop chatting while my brain struggles to reorganise all my expectations in the light of this capture. It takes several seconds for the realisation to hit home – on all previous occasions ISON has been invisible in the viewfinder, invisible in binoculars, invisible even in small telescopes. The best so far has been a faint smear in the camera frame, gathered at high ISO and long exposure. I let out a long whispering sigh of “Ooooooooohhhhhh Gotcha!” and walk the few steps in silent anticipation to show Stuart the iPad image. What the …..? Take a look at that, my friend, we’ve got ourselves a comet. Suddenly we are like excited schoolboys, chuckling, giggling, I even dance a little soft shoe shuffle in celebration. Now we start shouting at the clouds, there must be a gap coming soon? I hurry to realign the camera very slightly and catch ISON mid frame…

Dead centre. Perfect. Only the one frame, then the clouds fill the gap. For a moment I rejoice in my good fortune to be in the right place, at the right time, camera mounted and pointing in the right direction, mount aligned well enough for this 30 second exposure (yes, this version has been calibrated with dark and flat frames in PixInsight, and histogram stretched to improve contrast and minimise the urban glow on the clouds, but it’s still a single frame). Then I remind myself it’s not good fortune, is it? It’s thinking, planning, preparing and practising. It’s taking notes of every previous comet shot and thinking how the camera, lens and exposure settings influenced the final picture. Let’s not forget all the nights of going out and coming home disappointed. It’s setting that alarm clock again and actually getting up, loading up, going out, setting up, being ready, waiting for the moment, and pressing the shutter. Yes, pressing the shutter! I hadn’t even set up the remote trigger when this gap appeared in the cloud. This one, I took by hand.

There must have been hundreds of photos taken of ISON around the world that night, and many more in the weeks surrounding perihelion. Some of these have revealed exquisite detail in this visitor to our skies, not to mention the contribution they make to scientific data gathering. Anyone stumbling upon this photo in that context, will probably give it no more than a few seconds then click on by. It’s really not that good, but… it’s mine. I took it with my trusty Nikon and an old 300mm lens. I can even see some detail in the tail. All those nights of practice and rehearsal chasing PANSTARRS paid off. After ISON had its outburst on 14 November, we were mostly clouded over. Then the full Moon filled the night sky with light, and a few days later, ISON had its fateful rendezvous with the Sun. This particular photo opportunity will never come round again. From where I live, this might have been the one gap in the clouds that allowed one good shot of ISON between outburst and perihelion. One chance, one shot, and I got it.

PS. More practice with PixInsight and stacking the other frames I took that morning, has culminated in this version, which I don’t expect to improve. The embedded credit was added, if I might be permitted a name-dropping little boast, at NASA’s request so that they could circulate it in their outreach work. That’s the cherry on the icing on the cake.