The night after my encounter with the noctilucent clouds, we were again presented with a clear sky in Cumbria. I decided to have a last go at the increasingly remote target of PANSTARRS from my back yard, not exactly the darkest of sites. Next door is a small hotel, and the all-night corridor light is behind a window with no curtain. There is some intrusion from the street lights, and when the council staff in the offices behind the house leave for the night, they often leave the lights on. Finally, if the Fire Station or Ambulance Station do their night test drill, there can be every kind of light pouring into the yard.

However, a clear forecast tempted me to try setting up the system and leaving it running all night. A guarantee of no rain convinced me this would be okay. Of course, only the middle part of the night would be even vaguely dark (the Sun would never be more than 13 degrees below the horizon), but at least I would fill that darkish hour with frames and not have to stay up all night.

Balancing the RA axis of the mount took on a new importance. Remember, this is a second hand EQ3-2, tracking but unguided. Normally I would set the counter weight in an optimum position and ensure it was slightly heavy against the turn of the motor, using a ball & socket mount to retain flexibility in camera direction and orientation. One of the advantages of sitting by the system while gathering shots, is that the RA axis can be moved back to the optimum position. Leaving it running all night meant that the optimum had to survive about six hours or more.

300mm f/5.6, ISO 3200 5 min.

This is a JPEG of the unprocessed RAW frame from about 1am. You can see how much background light needs to be eliminated. The level of humidity in the air made this an extremely difficult task.

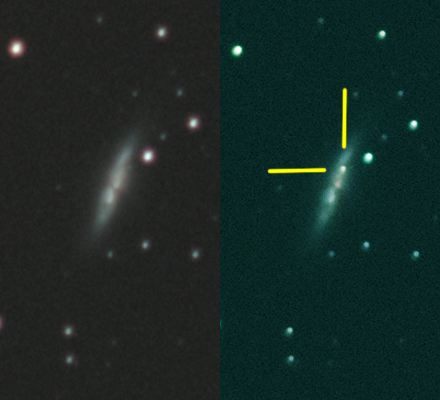

300mm f/5.6, ISO 3200, 15 x 5 min.

15 frames stacked in DSS on both stars and comet.

Deep Sky Stacker (“DSS”) lets you stack the frames by reference to the stars, or the comet, or both. In stacking for both, DSS makes two separate stacks. It then selects the stacked comet (eliminating the accompanying star trails) and inserts it in the reference frame for the stacked stars (eliminating the accompanying trailed comet). A significant loss of quality results, probably not helped by the humidity in the air.

300mm f/5.6, ISO 3200, 15 x 5 min.

15 frames stacked in DSS on the comet.

Stacking only on the comet avoids this loss of quality – and retains a more dynamic feel to the picture, in my view, showing clearly that the comet is moving against the star background. This is my preferred setting, and my favourite shot of this page. The tail is slicing past Yildun (Mag 4.3), some 2 degrees 33 minutes of arc away. Given that PANSTARRS is 1.86 AU away from Earth in this photo, that angle represents about 12.4 million kilometres, and the visible tail must therefore be about 15 million kilometres long. Visible, that is, at 5 minutes exposure. At Mag 9.5, PANSTARRS is invisible to the naked eye.

I wondered whether the choice of ISO 3200 was excessive. The comet’s core is burned out on the screen, and there is little dynamic range in the picture. Three nights later, I got a second chance at the same experiment. This time I reduced the ISO to 400, and the humidity in the night air was a little lower anyway.

300mm f/5.6, ISO 400, 5 min.

This is a sample unprocessed frame from about 1am again. This time, I stacked only the 11 frames from the darkest hour.

300mm f/5.6, ISO 400, 11 x 5 min.

11 frames stacked in DSS on stars and comet.

The quality of the result is still very hard to control when stacking on both stars and comet, but there is a definite improvement in dynamic range compared with the ISO 3200 version. That’s Urodelus (Mag 4.2) in the bottom right corner, by the way.

300mm f/5.6, ISO 400, 11 x 5 min.

11 frames stacked in DSS on the stars alone.

Stacking on the stars shows the comet’s movement, but blurs its important detail.

300mm f/5.6, ISO 400, 11 x 5 min.

11 frames stacked in DSS on the comet alone.

Stacking on the comet reveals its movement against the stars in a more dynamic way. As for the reduced ISO, I think the dynamic range might be better, but there is less information overall. On balance I prefer the ISO 3200, which is not surprising for a Mag 9.5 object using 5-minute subframes.

Anyway, the kit survived being left out all night, for two nights, which bodes well for when the nights get longer again. That is definitely my last attempt at PANSTARRS. It has been great fun, with cloud dodging, high humidity and low altitude at the key stage of passing M31, followed by increasingly light nights as it climbed towards the celestial pole. It best, it has been a joy to watch and to capture. Even at its most frustrating, it has given me bags of practice and experience to fall back on when ISON arrives this autumn.